Are Allegories a Good Idea?

Literature is full of allegories about all kinds of things. Although for most people, today, an allegory means a story based on or inspired by some religious theme, idea, or teaching, an allegory can be any kind of fable that tries to teach or inspire particular motives. Allegories are highly controversial, with some people strongly supportive, while others avoid them at all costs. Even like-minded people are sometimes at odds. For example, JRR Tolkien detested allegories, while CS Lewis clearly loved them.

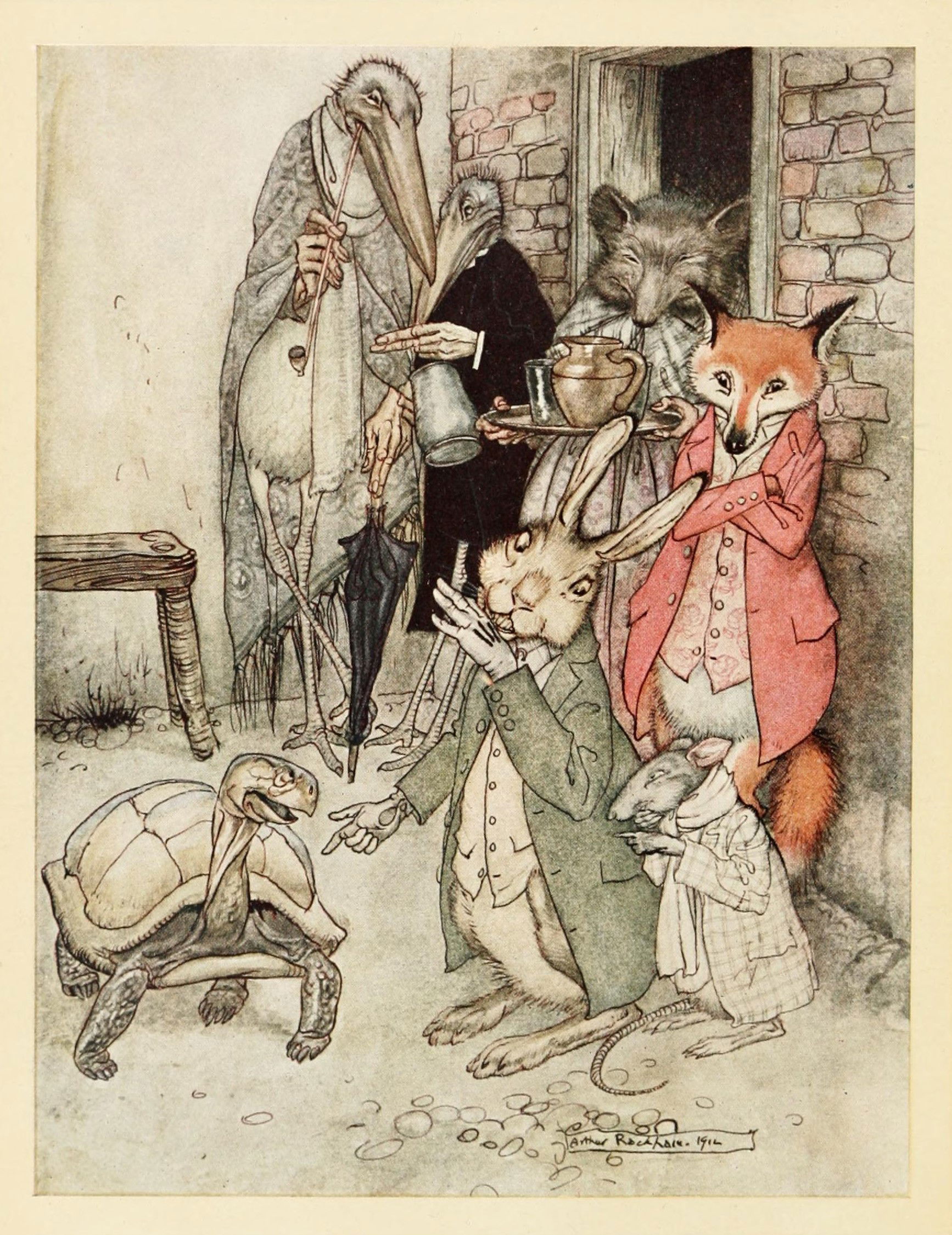

A key inner controversy among more conservative, religious-minded people is whether or not content is appropriate. Many, particularly parents, believe that a Christian allegory is the only wholesome option. Sadly, most authors think so as well. they feel that either it has to be an allegory or a completely secular work for the non-religious people. This all-or-nothing mentality alienates the culture of book buying, selling, and writing into two groups: Christian and Mainstream. The same can be seen in the film and music industry. However, the great division does not have to be as black and white as most people would think. Most books and films have some underlying theme or purpose, so it could be argued that any work of fiction is in fact an allegory. However, when practically speaking a true allegory is a story in which characters, places, and the overall plot revolves around and is based on real-life events and lessons. This means that each main character either represents someone or something, on the objective level. For example, in the Biblical, Parable of the Sower Mathew 13:1-9 each type of soil symbolizes a type of person. Similarly, Aesop's Fables are a series of lessons, told in short stories, often involving talking animals. in many editions, each story will have a wise proverb at the end like "Slow and steady wins the race," to further bring the message home to the readers.

That does not mean that there should be only one message and that is it. On the contrary, a good allegory should have many different levels of interpretation. This is especially true for longer books and stories. It is rather an easy thing to make an allegory that is simple to interpret, while far more difficult to create a subtle symbolism. I am not a fan of a book or film that is easy to decipher. Often Christian allegories are painfully obvious copies of Bible stories with few original ideas. If the story you plan to write is an allegory don't make it obvious. On the contrary, hide the symbolism so that most people at first will not even notice. Although you might think that defeats the entire purpose of making it an allegory, it doesn't at all. A good allegory will make readers think about what the story means both objectively and subjectively. Even Jesus' disciples often did not understand the meaning of his parables. Many people for years have interpreted the possible meanings of classic literature, like the Greek myths or the works of William Shakespeare.

I prefer a subtle symbolism, rather than allegory, and agree with this quote from JRR Tolkien, “I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence. I much prefer history – true or feigned– with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers. I think that many confuse applicability with allegory, but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed domination of the author.”

Rather than trying to mirror some specific lessons of them, I try to intertwine history and myth, virtue, and vice, triumph, and tragedy of human existence. If your story is an allegory, make sure that it is hidden well enough that people will have to think about it for a while. The more people are focused on something, the more they will want. Not only will this build up suspense, and mystery, but if you plan on making sequels it will make the readers interested in style.